Firebreak Forest

Draw firebreaks; watch forests grow, ignite, compartmentalize, recover

Firebreak Forest is a small, interactive simulation toy based on the classic Drossel–Schwabl forest-fire model. It’s a simple world where trees appear, fires ignite, and burning spreads across a grid—except here you can also draw firebreak lines that interrupt fire propagation. The result is a playful, visual way to explore how local rules create global patterns, and how small interventions can reshape the dynamics of an entire system.

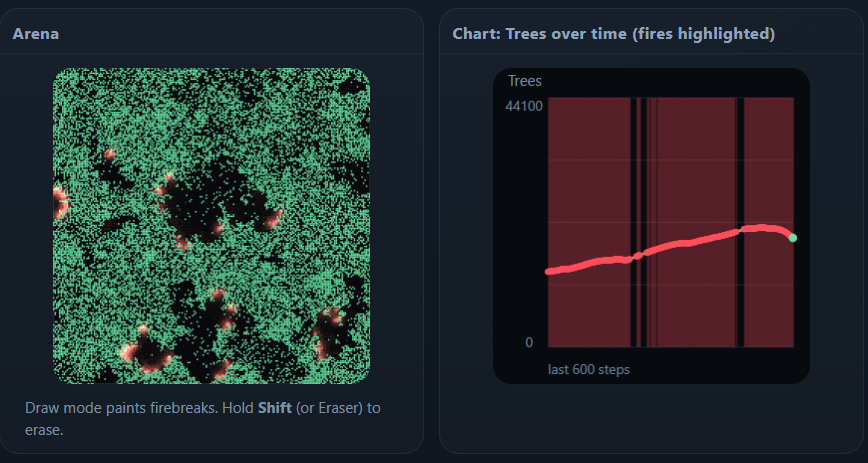

At its core, the simulation runs on a square lattice (“arena”) made of many cells. Each cell can be empty, contain a tree, or be burning. Time advances in discrete steps. On each step, three processes happen through basic probabilistic rules:

Growth: empty cells can become trees.

Ignition: trees can catch fire spontaneously (“lightning”).

Spread: trees can ignite if a neighboring cell is burning.

Even with these minimal ingredients, the system shows surprisingly rich behavior. Long quiet periods with slow regrowth can be interrupted by sudden cascades of burning that wipe out large regions, followed again by recovery. This kind of “punctuated” dynamics is a hallmark of many complex systems: local interactions accumulate tension until a threshold is crossed, and then a release happens quickly.

What makes Firebreak Forest different from a plain DS model demo is that it includes a firebreak concept. A firebreak is a user-drawn barrier cell. Firebreak cells do not grow trees, do not burn, and (most importantly) do not transmit fire across them. When you paint a line of firebreaks, you’re carving the arena into compartments. Fire can still happen inside a compartment, but the barrier reduces connectivity, making it harder for a single ignition to spread into a huge event. This gives you an intuitive way to see how geometry and connectivity influence the size and frequency of cascades.

The controls are intentionally minimal:

Probability of growth (p): how likely an empty cell becomes a tree at each step.

Probability of fire onset (f): how likely a tree ignites spontaneously at each step.

Grid size: the resolution of the arena.

Drawing mode + brush size: to paint or erase firebreak lines.

You can start, pause, and reset the simulation. Reset clears the arena back to empty (black) so you can watch patterns emerge from nothing. If “ignite on click” is enabled, you can also manually start a fire by clicking a tree, which is helpful for testing how a particular firebreak design behaves.

A simple chart runs alongside the arena: it plots the number of trees over time, and highlights time steps where fire activity occurs. This is useful because the arena can look busy, but the chart tells you the story at a glance: steady growth ramps up the tree count, then fire episodes pull it down. With firebreaks, you’ll often see more frequent but smaller dips, or long stable stretches depending on how you partition the space.

A good way to play is to start with no firebreaks and observe the “baseline” rhythm. Then draw a single line splitting the arena in half. You should see larger fires become less common because a burning front cannot cross your barrier. Next, try dividing the arena into several compartments, like a grid of blocks. You’ll often get localized burn events that don’t dominate the whole map. Finally, experiment with narrow corridors or “gates” between compartments; tiny connections can make a big difference, because they restore pathways for spread.

This toy is not meant to be a faithful wildfire forecast tool. Real wildfires involve wind, fuel moisture, terrain, ember spotting, suppression tactics, and many other processes. The DS model is deliberately abstract: it strips things down until only the core idea remains—growth competes with rare ignition, and local spread amplifies ignition into events. Firebreaks here are also idealized “perfect barriers.” In reality, firebreak effectiveness depends on width, fuels, topography, and conditions. The value of the toy is conceptual: it helps build intuition for how connectivity, compartmentalization, and random shocks can shape system-level risk.

If you like thinking in systems terms, you can interpret Firebreak Forest as more than trees and fire:

Trees are “stored potential” (fuel, resources, density, connectivity).

Lightning is a random shock.

Spread is contagion through a network.

Firebreaks are structure or policy: constraints that rewire connectivity.

Seen that way, the toy resembles many phenomena: cascading failures in power grids, meme spread in social networks, traffic jams, computer worms, financial contagion, or any setting where local interaction can turn small incidents into large events. The specifics differ, but the pattern of growth + rare shocks + propagation + recovery is common.

The visual effects (glow, sparks, embers) are included for clarity and drama, but they are cosmetic. They don’t change the underlying rules. They’re there to make burning easier to perceive, and to give the simulation a lively feel without speeding up the dynamics.

If you want a “challenge mode,” set growth low and fire onset very low, then try to design firebreak layouts that keep the system from ever producing a large burn event. You can also flip the perspective: try to create a design where a single ignition can still propagate widely (by preserving connections), or where the forest can recover quickly after fires (by leaving enough open area for regrowth). Because the rules are simple and stochastic, you won’t get the same outcome every time—part of the fun is seeing how randomness interacts with your structure.

Firebreak Forest is best enjoyed as a tiny sandbox: click start, watch patterns form, intervene with a few strokes, and see how the system responds. Sometimes small changes feel pointless; other times one thin line completely changes the behavior. That’s the central lesson: in systems driven by connectivity, geometry matters, and “where” you intervene can be as important as “how much” you intervene.